Choosing a Statistical Test

Statistical tests are just tools. Using the correct tool for a specific job is much easier, fun, and useful than using the wrong tool. Learning how to select the correct tool takes practice. Sometimes several different tools could be used and address slightly different questions of nuances to the same question. In some cases there is no single perfect tool and we must settle for an imperfect one, understanding its limitations.

Statistics is an area of active research and development, with new tools being developed and tested. Statisticians often disagree about these new tools and how useful they are.

There are several ways to approach thinking about what test is most appropriate.

The following questions should be useful in guiding what tests are better or worse for your question.

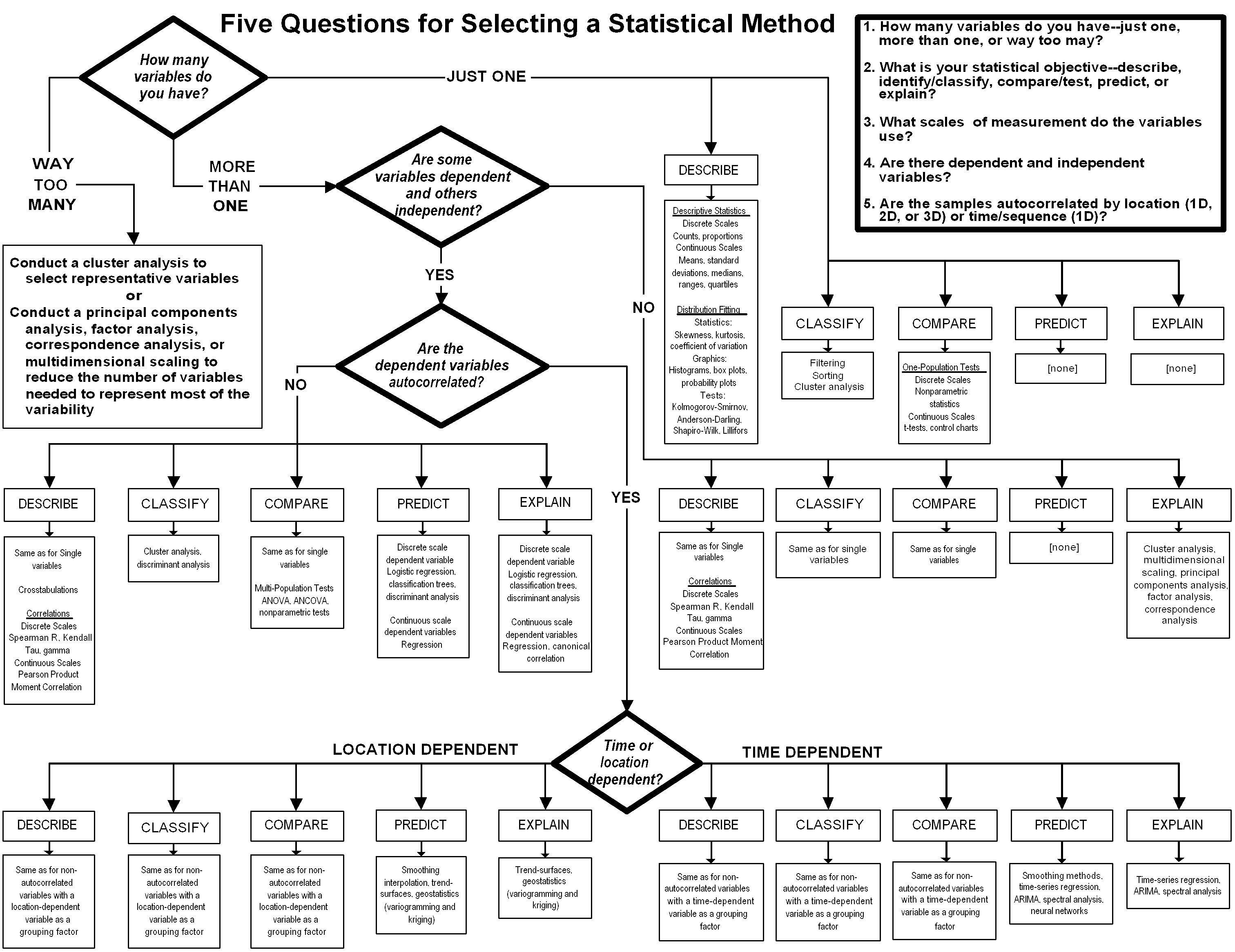

1. What is your (statistical) objective?

There are various ways of using statistics.

The following list moves from the easiest to the hardest, practically, computationally, and philosophically.

-

Description Describes and characterizes populations and samples using descriptive statistics, graphs, and maps (e.g., opinion surveys, polls, population census)

-

Classification Classifying, identifying and categorizing a sample based on its characters uses descriptive statistics, graphics, and multivariate techniques (e.g., drug effectiveness).

-

Comparison Looks for differences between populations, samples, or reference values using ANOVA and similar tests (e.g, species identification and description, identifying criminals and terrorists).

-

Prediction We can predict future measurements using regression, time series analysis or spatial interpolation (e.g., weather, election results, student success).

-

Explanation Here we look for the most important drivers of variation in the data to try and understand what is going on (a lot of academic research … e.g., does climate change affect species phenology? does conservation intervention x actually work?).

2. How many variables do you have?

Do you have one variable, two, more than two, or a lot?

3. What kind of data are they?

Discrete

Discrete data can only take particular values, with no grey area in between.

-

Categorical/nominal counts or frequencies of things in two or more groups/categories, with no intrinsic ordering to these categories (e.g., eye colour, gender, species).

-

Ordinal counts or frequencies of things in two or more groups/categories, but with intrinsic ordering to these categories (e.g., level of education: elementary school, high school, college, post-graduate).

-

Interval counts or frequencies of things in two or more groups/categories, with intrinsic ordering to these categories, and where the spacing between categories is equal (e.g., equal-sized groups of age: 0-9, 10-19, 20-29, …; income, etc.).

-

Integer Numeric data can be discrete if we are counting whole things (e.g., the number of apples), even if there is potentially an infinite number of these things.

Continuous

Continuous data are not restricted to any particular set of values. Continuous data can take any value over a continuous range. These data are always essentially numeric (e.g., height, weight, length).

Continuous data can be treated as discrete by binning, or putting each value into a specific category that encompasses a range of data. This data is then interval data (see above).

4. Is there a distinction between dependent and independent variables?

Is there some a priori reason why you think that one variable has a direct effect on the other? If you are trying to predict or explain something, you are assuming some causality.

5. Are the samples autocorrelated?

Observations may be correlated with each other in some way (i.e., autocorrelated).

-

Time if you take repeated measurements of the same thing, e.g., a persons height every year, the temperature every hour, the DBH of a tree every month.

-

Space if you measure the distribution of nutrients or minerals in soil, household income throughout a town.

In these two cases, temporal or spatial autocorrelation has little-to-no effect on the coefficient estimates in your statistical models, but it will affect the variance (standard deviation, standard errors) that are calculated, and therefore also any p-values and statistical significance.

- Sequence if you use the same equipment to take measurements and that equipment slowly drifts out of calibration, or if you take light measurements at the forest floor as the sun comes up.

In contrast to temporal and spatial autocorrelation, sequential autocorrelation will obviously affect the values you obtain.

How to choose a Test: Table!

| No. variables | Response | 1 | >1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response type: | factor | numeric | numeric | binomial | count | numeric | numeric | |

| Predictors | Predictor type: | factor | factor | numeric | fac/num | fac/num | numeric | factor |

| 1 | binom.test() |

mean(), sd(), hist() |

regression, lm(); correlation, cor() |

generalized linear model (logistic), glm( ..., family = 'binomial') |

generalized linear model (Poisson), glm( ..., family = 'Poisson') |

multivariate stats | multivariate stats | |

| 2 | prop.test(), chisq.test() |

t.test() |

multiple regression, lm() |

generalized linear model (logistic), glm( ..., family = 'binomial') |

generalized linear model (Poisson), glm( ..., family = 'Poisson') |

multivariate stats | multivariate stats | |

| >2 | prop.test(), chisq.test() |

ANOVA, aov(), lm() |

multiple regression, lm() |

generalized linear model (logistic), glm( ..., family = 'binomial') |

generalized linear model (Poisson), glm( ..., family = 'Poisson') |

multivariate stats | multivariate stats |

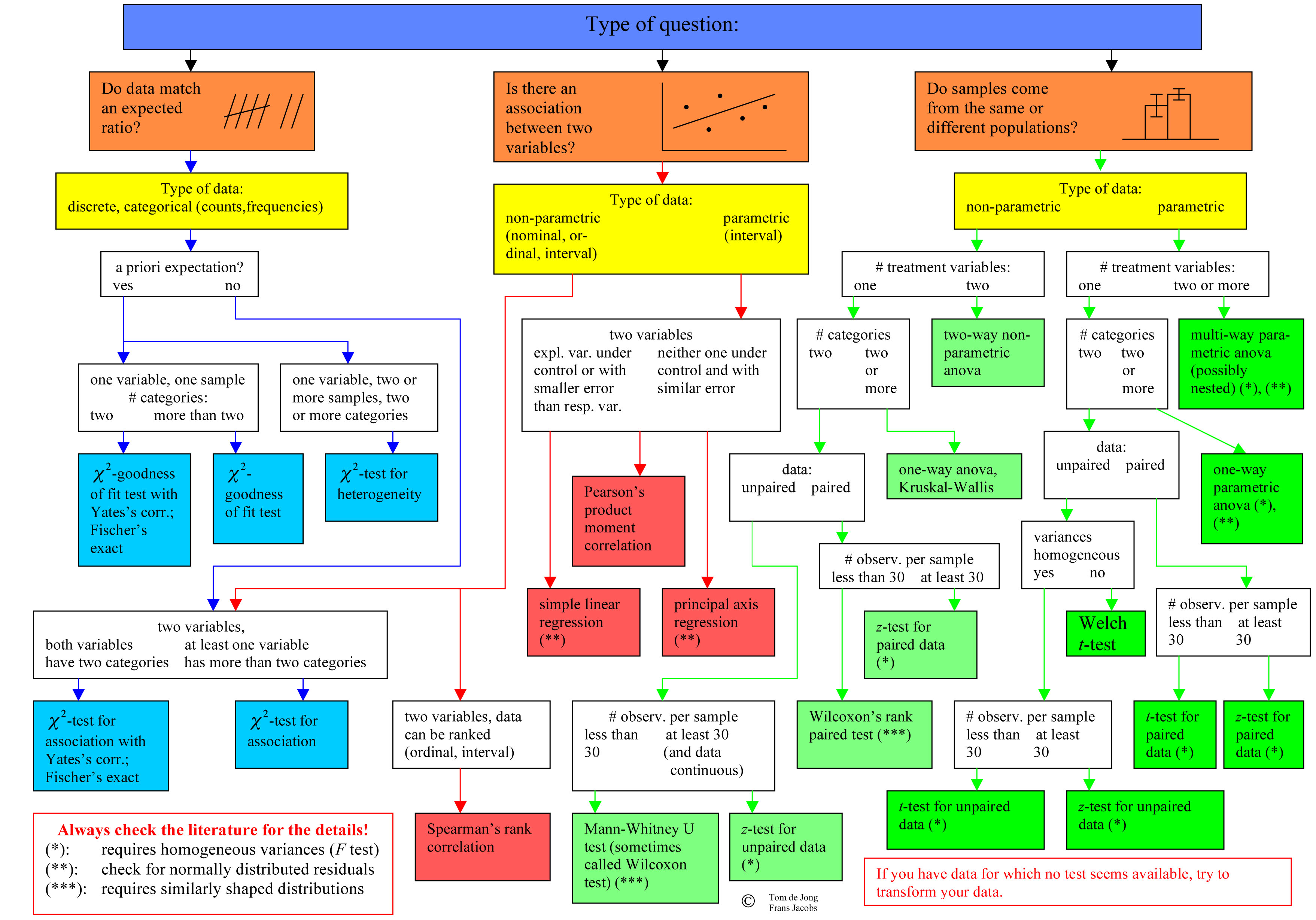

How to Choose a Test: Flowcharts!

1. Based on the five questions.

2. Based on the data.

Updated 2018-10-01